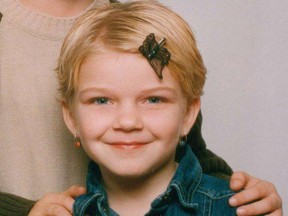

Juror at trial of Michael Rafferty, found guilty of killing Tori Stafford, suffering PTSD, looking for compensation

Article content

For more than two months, she watched, listened and pondered over the trial of a man who brutally raped and murdered a Woodstock schoolgirl.

It was the personal toll of the 2012 Michael Rafferty trial that one of the 12 jurors never expected — a severe case of post-traumatic stress disorder that’s shaken her to her core.

Symptoms have been debilitating, she says, including memory loss, bouts of extreme anger and a shopping addiction that drained her retirement savings and children’s education plans.

She has recurring visions of being at the crime scene, watching eight-year-old Victoria (Tori) Stafford die — and being unable to save her.

“It’s been horrible. It’s a nightmare,” she said Tuesday. “This has been hell.”

The juror’s identity is protected by court order.

But any recognition of her pain as a juror has been denied by the justice system and the arm of the provincial government whose purpose is to financially compensate victims of crime.

Next month, the Ontario Court of Appeal will be asked if the 57-year-old Londoner and single mother of two is also a victim of Rafferty’s extreme violence and entitled to compensation from the Criminal Injuries Compensation Board.

The test case could redefine what it means to be a victim under compensation board rules and have implications to how juries in significantly troubling cases are handled.

Lawyer Barbara Legate of Legate and Associates, who is representing the woman, said the community owes jurors help.

“We asked a lot of all those jurors,” Legate said. “At the end of the trial, what we ask of them should end, but if it doesn’t, why do we ask the juror to deal with that all by his or herself?

“I say we ask everybody to bear that burden because they are doing a service for us.”

So far, the board and the Divisional Court of the Superior Court of Justice have rejected the juror’s claim, saying she doesn’t qualify under the rules.

But Legate will argue her client was an involuntary member of the court process performing her civic duty and was required by law to participate in the trial. Under the Compensation for Victims of Crime Act, she is a victim of crime and entitled to help for injuries “resulting from” the crime heard at the trial, Legate said.

The compensation board, in its written argument to the appeal court, fears compensating a juror would open the floodgates so anyone who sits through a extremely violent trial — judges, court staff, prosecutors, defence lawyers, police and journalists — will want compensation.

It argued that people who claim nervous shock with no physical injury or proximity to the crime shouldn’t be considered victims.

The juror, it argued, suffered her PTSD from hearing the evidence at the trial, not the crime itself.

The juror was a perfect selection for the trial. She had just moved to London, had no knowledge of the little girl’s death and went into the trial with a clean slate.

She said that she knew at the time of the verdict that something was wrong. “At the end, I bubbled up,” she said. “It was like you suppress everything for so long, it’s over.”

She accepted some help through the police after the trial, but it wasn’t going to be enough. She had been balancing her jury duties with her job throughout the trial. She decided that she and her two children needed a vacation and they headed to Niagara Falls for a week.

She was already experiencing some memory loss, but it was there she said she “just blew” and her anger started to pour out. Her doctor ordered her off work.

The woman said she got a dog and wanted to buy a horse. She said her finances were in such shambles she had to sell her home and move into something smaller.

She reached out to prosecutor Kevin Gowdey from the Crown’s office, who linked her up with help at Victoria Hospital. And, after she and another juror did their version of “Tori’s Walk,” revisiting all the places the little girl was before she died, she visited Woodstock police.

“I felt like I was walking on a treadmill in a glass bubble, all foggy and I can’t get off and I can’t get out,” she said. “I wanted help so bad so I could start living my life again.”

She said other jurors have experienced the same stress.

Her appeal will be heard Nov. 8 in Toronto.